Jan Kamenský1,2, Jan Kulhánek1

1Faculty of Science, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic

2Czech Geological Survey, Prague, Czech Republic

The SGA Student Chapter Prague honours its long-standing tradition of organizing an annual autumn field trip, and this year was no exception. Scheduled for late autumn (November 17–19, 2023) the trip was strategically planned to allow the participation of first-year bachelor geology students. Our destination of choice this year was the captivating mineralogical sites and historically significant localities of the Ore Mountains in the NW Czech Republic. Sixteen students participated in the excursion, led by chapter advisor Dr. Jan Kulhánek and president Jiří Klepp.

Geological settings:

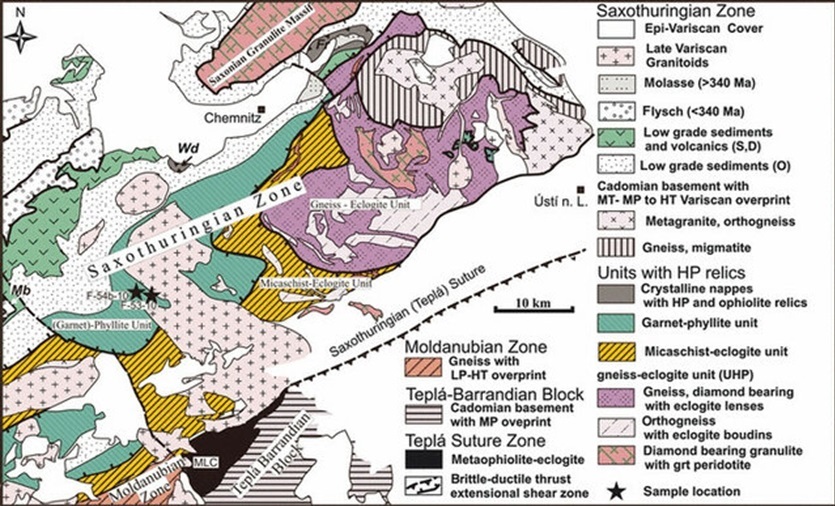

The European Variscan Belt finds its easternmost exposure in Central Europe, shaping the Bohemian Massif. The Ore Mountains, a historically significant mining region, are situated within the Saxothuringian Zone (SZ), the SW–NE-trending belt which extends in the NW part of the Bohemian Massif (see Figure 1). The SZ is tectonically separated from the Teplá-Barrandien unit (TBU), lying along its southeastern border. Within this framework, the SZ represents the lower plate that underwent subduction beneath the hanging wall of the TBU along a prominent Variscan suture (e.g., Franke, 1989; Jouvent et al., 2022). Comprising primarily complexly over-thrusted and over-folded metamorphic nappe units of diverse metamorphic grades, the Ore Mountains exemplify accretionary wedge formation between the SZ and TBU. From the deeper levels of the subduction channel, rocks of high- to ultra-high-pressure metamorphism, such as eclogites, blueschists, and coesite- or diamond-bearing paragneisses and granulites, have been exhumed (see Jouvent et al., 2022). The Variscian and post-Variscan tectono-magmatic activities are closely associated with the formation and subsequent remobilization of the polymetallic ores in the area. The Bohemian Massif also underwent significant magmatic and volcanic activity during the Cenozoic era. Much of this volcanic activity was concentrated along the Eger Rift, aligning with the Saxothuringian Variscan suture, and constituting the northeastern branch of the European Cenozoic Rift System (Ulrych et al., 2011). Evidence of this volcanic activity is also observable in the Ore Mountains, where well-preserved remnants of Cenozoic volcanism, erupting through the metamorphic basement, form prominent hills in the surrounding landscape.

1st day:

The field trip began at the hut at Boží Dar, an old mining town near the Czech-German border, on the evening of November 16, 2023, which served as our base for the entire excursion. The following morning, November 17th, visit of several localities followed after the broad geological introduction at the hut. Our first visit took us to Abertamy town, where we visited private collection of mining artifacts and ore minerals sourced from the surrounding localities, such as Abertamy, Jáchymov, or Stříbro.

Continuing our trip, we embarked on a brief tour of the surrounding of the closed Mauriticius mine, the oldest tin mine in the Czech part of the Ore Mountains, with its origins tracing back to the 16th century. This historical site, now open for tourists, offered a glimpse into centuries-old mining practices. Our time at the Mauriticius mine also afforded opportunities for mineralogical sampling, with notable finds including specimens of hematite and quartz (amethyst variety) sourced from the mine’s excavation sites and observation of the metasomatic process causing formation of greisens and associated tin mineralization along the veins cutting the granitic body. In the vicinity of the Mauritius mine was also possible to observe Schnepp’s pinge, a sinkhole formed atop the remnants of a former tin mine, following the steep vein planar orientation. In the vicinity of the Mauritius mine was also possible to observe Schnepp’s pinge, a sinkhole formed atop the remnants of a former tin mine, following the steep vein planar orientation.

Our itinerary then led us beyond the confines of the Ore Mountains to the significant mineralogical site of Huber Stock, situated near Horní Slavkov (GPS: 50° 8′ 19″ N, 12° 48′ 28″ E). Geologically characterized as a greisenized plutonic elevation, Huber Stock stands as a testament to the region’s diverse mineral wealth, with notable occurrences of tungsten and tin mineralization. Historical records indicate subsurface mining activities dating back to the 13th century, with a notable period of pit quarry operations from 1973 to 1976. Notably, Huber Stock boasts a rich mineralogical diversity, with 117 documented minerals, including five designated type localities, underscoring its significance in the field of mineralogy.

2nd day:

Our second day of the trip began with a visit to Meluzína Hill, a prominent feature in the landscape. Comprised mainly of eclogite, a high- to ultra-high metamorphic rock, Meluzína Hill offers insights into the region’s geological history. Originating from the subducted oceanic Saxothuringian plate, the rock was subducted deep beneath the TBU plate into the Earth’s mantle before being exhumated back to the crustal levels, shedding light on past plate tectonic processes. Discussions at the site focused on reconstructing the pressure-temperature conditions that shaped these rocks, along with an examination of the “atoll texture” of garnets commonly observed in metamorphic rocks of the area.

Our journey then took us to Horní Halže, where we explored remnants of iron ore mining. Here, a small heap served as a reminder of the area’s industrial past, with quartz veins often displaying a distinct violet color, earning the site the nickname “Amethyst heap.”

Next, we visited Mědník Hill in Měděnec, where iron ore extraction occurred from the 15th to the 19th century. The site’s skarn body, associated with the polymetallic mineralization, showcased visible garnet, diopside, and magnetite grains, providing insights into the region’s mining heritage.

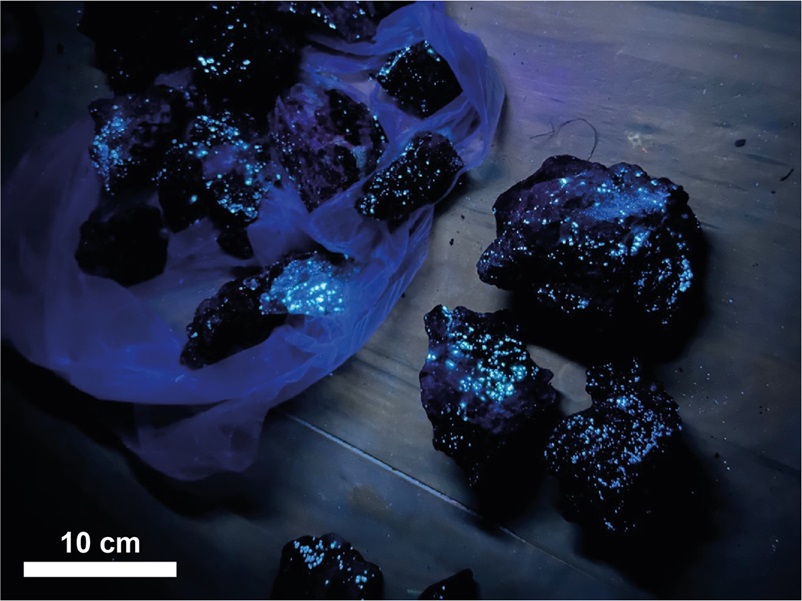

Finally, we arrived at Volyně u Kadaně, a forested area housing loose rocks indicative of mining activity focused on a quartz hydrothermal vein renowned for the associated fluorine and tungsten mineralization. Characterized by a brecciated and honeycombed texture due to fluorite leaching, the vein revealed small fluorite and scheelite crystals, well-recognizable under the short-wave UV light (Figure 2).

3rd day:

Our final day began with a visit to the Kovářská site, where we examined fluorite-barite veins that were actively mined in the 1970s and 1980s. Though mining activities have ceased, remnants of these veins remain, offering opportunities for mineral collection. Participants had the chance to collect specimens of fluorite and barite from surrounding mining heaps, providing tangible connections to the area’s mining history. Moving on, we also visited a reclaimed heap near Hradiště u Kadaně, focusing on collecting hematite crystals, characteristic of the area. Our excursion concluded at the Blahuňov locality, known for hydrothermal veins cutting through gneiss formations. Here, participants observed collectible fluorite-quartz specimens, with the quartz exhibiting a carnelian variety.

With our cars loaded with mineral samples, we concluded our excursion and returned to Prague, reflecting on our experiences over the past three days. Our exploration had not only yielded valuable specimens but also deepened our understanding of the mining and geological history of the Ore mountains.

Acknowledgments:

We wish to extend our gratitude to the company Severočeské uhelné doly a.s. and to the UNESCO International Geoscience Programme (project ČNK-IGCP 637) for their financial support.

References:

Faryad, S. W., & Kachlík, V., 2013. New evidence of blueschist facies rocks and their geotectonic implication for Variscan suture (s) in the Bohemian Massif. Journal of metamorphic Geology, 31(1), 63–82.

Franke, W., 1989. Tectonostratigraphic units in the Variscan belt of central Europe. Geological Society of America Special Paper, 230, 67–90.

Jouvent, M., Lexa, O., Peřestý, V., & Jeřábek, P., 2022. New constraints on the tectonometamorphic evolution of the Erzgebirge orogenic wedge (Saxothuringian Domain, Bohemian Massif). Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 40(4), 687–715.

Ulrych, J., Dostál, J., Adamovič, J., Jelínek, E., Špaček, P., Hegner, E., & Balogh, K., 2011. Recurrent Cenozoic volcanic activity in the Bohemian Massif (Czech Republic). Lithos, 123, 133–144.